Follow the Money: Mapping Local Public Health Investments to Drive Real Change

The world is full of wicked problems – those persistent, complex issues that defy easy solutions and quietly erode the health and potential of people who call this place our home. Think opioid use, homelessness, poverty, lack of access to affordable health care, and housing stability. These are problems that shift over time, resist linear solutions, and cannot be solved by any one program or profession alone. We all know them. We all live with them.

But what if we told you that the only real way to tackle these challenges – actually tackle them – was through strategic collective action? That means organizations with different missions, cities with different priorities, and people with differing politics aligning around common goals, shared measures, and coordinated action.

Yes, that kind of collaboration is hard. It’s even harder when every organization is working from its own mandate, funding stream, and set of reporting requirements. But here’s the thing: public health departments were built for this kind of work. Not to be the hero of the story, but to be the backbone. To support, align, coordinate, and inform. To build the system capacity that makes collective impact possible.

At Jackson County Public Health, we’ve been asking ourselves: What do we need to do our part better?

Part of the answer starts with money.

Why follow the money?

Public health departments often have a broad view of community needs, but not always a clear picture of how public health investments are being made – or where gaps persist. If we don’t understand how dollars move through our local safety net system, we can’t offer meaningful strategic insights to the policymakers, partners, and funders trying to strengthen it.

That’s why, in the spring of 2025, we partnered with KU public health student Ayomide Okosun to tackle a project we’d long been circling: mapping public investments in Jackson County’s health and social safety net.

It’s easy to say funding matters – but the process of actually following the money is messy. The safety net includes hundreds of organizations, dozens of funding streams, and systems that were never designed to be interoperable. It felt, at times, like trying to move from stargazing to actually flying a satellite.

But if public health can develop better tools to analyze, visualize, and advise on these funding flows, we can help change that. We can be a steward of smarter investment – not just an outside participant in the next grant cycle.

Our Analysis: Digging Into the Safety Net

Our initial work focused on answering two critical questions:

- Which organizations have consistently received safety net funding over the past five years?

- Are there organizations that have received funding from all three major Jackson County sources?

To answer these, we gathered and analyzed five years of data from:

- Jackson County Outside Agency Fund

- Children’s Services Fund

- Community Mental Health Fund

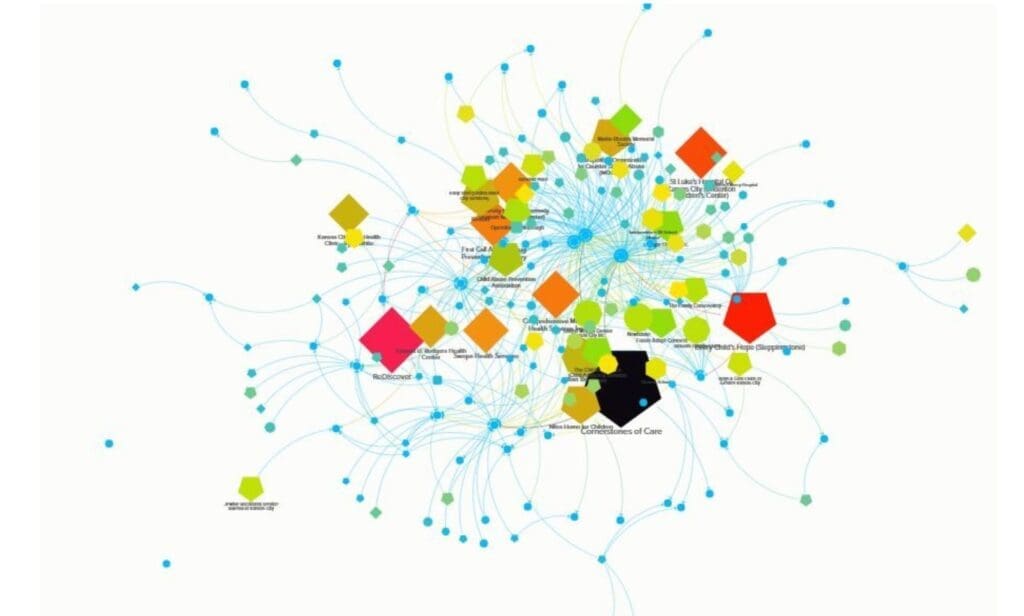

We categorized recipient organizations by type (e.g., community health, housing support, mental health services), then used Excel for data cleaning and KUMU for network visualization. The goal wasn’t just to report totals, but to uncover patterns – and make those patterns visible.

What We Found

Our visualizations revealed several key insights:

- Funding is consistently concentrated among certain types of organizations, especially those that serve vulnerable populations through comprehensive, wraparound approaches. Think: community health centers, EMS providers, and mental health programs.

- A smaller set of organizations received funding from all three sources, typically those with broad missions, strong infrastructure, and the ability to serve general populations over the long term.

These findings point to an important but under-discussed truth: access to funding is often a reflection of capacity, not just need or impact. That creates blind spots – and opportunities for public health to step in.

Why This Matters

Public health has a critical role to play in shaping how communities invest in their own well-being. Ayomide’s project showed how we can start doing that more intentionally by:

- Framing public investments as a coordinated portfolio of impact, rather than a patchwork of disconnected grants

- Tracking long-term trends to identify which needs are being met—and which are being overlooked

- Creating tools that help decision-makers see the whole system, not just the silo they operate in

This work is more than a one-off analysis. It’s part of a broader commitment to financial transparency, system stewardship, and equity-focused planning.

What’s Next?

We’re committing to making this kind of financial systems analysis a regular practice at Jackson County Public Health – an annual look at how local public health investments flow through our community health and social systems. But we also know this work can’t stop with us.

We need policy change that supports and rewards systems thinking – because funding and accountability structures shape behavior. If we want more collaboration, more alignment, and less duplication, we need to build that into how we fund and evaluate the work.

Here are some recommendations for policymakers and funders to help shift local systems toward effective, equity-driven collective action:

- Prioritize Funding for Organizations Participating in Collective Efforts: Wicked problems require big teamwork. We should prioritize funding for groups that are working with others across different sectors and regions, using shared goals and data. This kind of collaboration takes time, energy, and coordination—so our funding should reflect and support that effort.

- Fund Strategies, Not Just Organizations: Shift from funding individual agency outputs to supporting community-identified strategies. When priorities emerge from broad-based planning processes (like community health improvement plans or collective impact groups), align public funding to those shared goals.

- Embed Strong Evaluation Expectations in Collective Work: Invest in the infrastructure to evaluate systems-level impact, not just program outcomes. That means tracking shared indicators, monitoring for duplication, and assessing whether investments are truly filling gaps or reinforcing existing silos.

- Use Financial Mapping as an Ongoing Policy Tool: Support local public health and government entities in conducting regular funding flow analyses to inform decisions as a foundational public health activity. These tools help illuminate redundancy, surface unmet needs, and make the invisible parts of the system visible – especially fragmented safety net environments.

Public health has a unique vantage point, but it can’t do this alone. Systems stewardship is a shared responsibility – one that requires new expectations, new tools, and new accountability mechanisms. By aligning funding with shared values, we can move from a fragmented patchwork of programs to a coordinated system of care that reflects the needs and hopes of our communities.

Archives

- February 2026 (1)

- December 2025 (1)

- November 2025 (2)

- September 2025 (1)

- July 2025 (2)

- June 2025 (3)

- April 2025 (2)

- January 2025 (2)

- December 2024 (1)

- September 2024 (2)

- August 2024 (2)

- July 2024 (1)

- June 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (1)

- July 2023 (1)

- March 2023 (1)

- October 2022 (1)

- September 2022 (1)

- August 2022 (1)

- July 2022 (2)

- June 2022 (2)

- May 2022 (1)

- April 2022 (4)

- March 2022 (1)

- February 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- December 2021 (4)

- November 2021 (3)

- September 2021 (2)

- August 2021 (3)

- July 2021 (2)

- June 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (2)

- March 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (6)

- November 2020 (8)

- October 2020 (4)

- September 2020 (7)

- August 2020 (3)

- July 2020 (11)

- May 2020 (2)

- April 2020 (4)

- March 2020 (1)

Categories

- Communicable Disease (5)

- Clinical Services (19)

- Clinical Servcies (1)

- Health Promotions (74)

- Emergency Preparedness (8)